how to study the Bible: understand the genres

/In the history of this blog, three of the top five most-read posts have been related to the topic of knowing and studying God’s Word. I love nothing more than hearing someone say, “I’d love to know how to study the Bible for myself” - or, “I’ve been going to church and Bible studies for years but I’m just so hungry for MORE.”

The study of the Bible isn’t just for pastors and elders. God’s Word is not only accessible to those who spend a decade in seminary learning ancient languages. I’m thankful for the people in my life who showed me that I, too, could learn how to study it for myself - because I was (and still am) hungry.

If you are hungry, too, this series is for you.

How to study the Bible

Step Two: Organize it by genre.

The first step to a rich and thoughtful personal study of the Bible was simply to read it. But while we are taking that step, there are several others we can implement concurrently to ensure that we’re getting more than a surface skim of the text.

One of those steps is to know and understand each of the different genres of literature the Bible contains, and which books can be shelved under which genre. Although it’s important to read the whole Bible as a story, not every book within the Bible is best approached that way, and that’s where the genres come in handy.

I study the Bible from a seven-genre perspective, although some scholars might suggest that the number is greater or fewer. How many you use matters far less than knowing how to use them, so I’ll give a short overview of each genre category I use here:

Narrative

Our first genre is also the most voluminous in Scripture, and may go by the name of narrative, history, or biography. It is made up of just what its title would suggest: narratives. Stories. If you grew up in the church, as I did, a lot of your Sunday school lessons likely came out of this genre - Moses and the burning bush, Jonah and the great fish, Joseph’s coat of many colors.

Narrative literature makes up the stories of God’s work in and through ordinary people. The key word here is ordinary. When we read and study the books of narrative, one of the most important things we can do is avoid painting the characters in black-and-white terms. The Bible’s characters don’t fall neatly under “hero” and “villain” categories; everyone in the Bible, much like everyone in our present lives, has the ability to do both good and evil. The goal is not to moralize their stories, but to look for how God works to reveal Himself both because of and in spite of them.

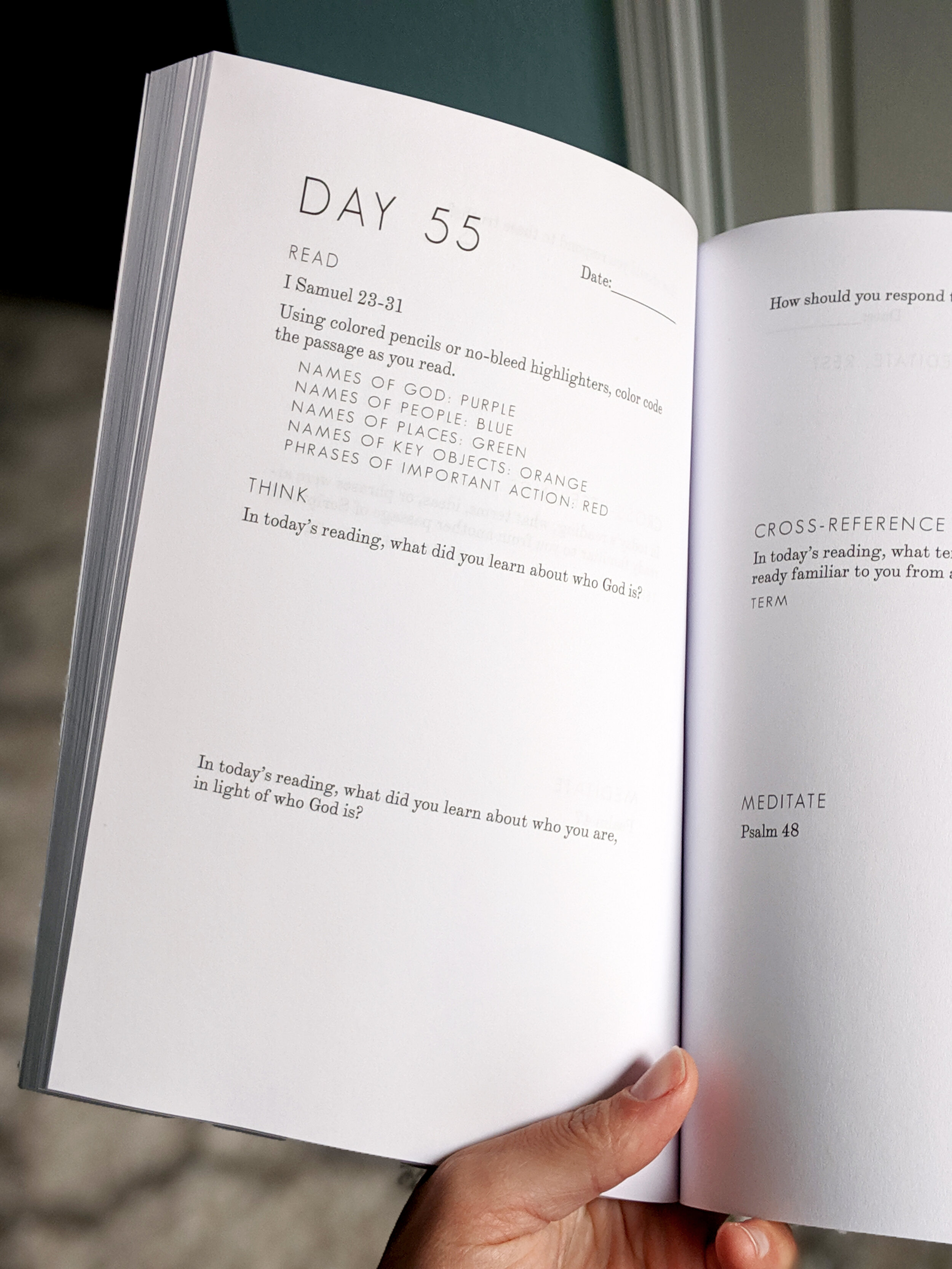

A helpful habit to add to your reading of narrative is a simple color coding routine, like the following:

Blue: Names of people

Purple: Names of God

Green: Names of places

Orange: Names of key objects

Red: Phrases of important action

This will help you comprehend the who, what, where, etc. that are so important to following the flow of a story. They’ll also make it easy for you to drop yourself into the middle of a narrative later on and remember all the key players at hand. (Note: Make sure to use no-bleed highlighters! Colored pencils also make a fantastic and very safe alternative.)

Law

Raise your hand if the Law is your favorite genre of literature. Anyone??

Probably not. But the Law of Israel gets a much worse rap than it deserves, mostly for the lack of understanding we have for its purpose. It’s a relatively tiny portion of the Bible - only around 70 chapters of the Bible’s 1,189 - and yet it’s an incredibly important piece of the puzzle.

Why? Because the legal literature of the Old Testament is the testimony of God’s character and holiness to the nation of Israel. Every command it contains is like a pane in the window through which we can begin, in our feeble and finite way, to comprehend God’s infinite character. Though the laws don’t pertain to us directly as Gentiles under the New Covenant, the principles they share with us of who God is and what He values are priceless.

When reading through the chapters of law, mark the divisions between each rule or legal topic and write a quick summary title of that rule in the margin. For example, you might label Exodus 22:21-24 “Oppression Law.” In the next chapter, Exodus 23:9 might get the very same title. This way, you can find out what God’s heart is on a huge diversity of issues, and refer back to them quickly and easily.

Wisdom

Wisdom literature can be the trickiest to organize, and therefore is the biggest reason that scholars’ genre counts differ. I use seven because I’m separating poetry and lament from wisdom, but the traditional understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures considers wisdom to be an umbrella term for all three categories. For the purpose of reading, that approach works perfectly fine, but I find that a bit more nuance is required for in-depth study. So I think of wisdom as its own category, containing three books (Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes), and poetry and lament as two of its sub-categories.

Wisdom literature gives voice to the search for God’s answers to man’s hardest questions. Often, this search is like an operation in mining, requiring a lot of hard work and risk to reap the rewards. Rarely is any neat and tidy answer reached, but great spiritual maturity and submission can be developed along the way.

It helps to read wisdom literature through the lens of the question each book is wrestling with:

Job: Does God have the right to my life?

Proverbs: What is God’s design for life?

Ecclesiastes: What is the meaning of life?

Poetry

A full third of the Bible’s content is written in poetic form, making this subset of wisdom literature far larger in volume than the wisdom category itself. Much of the size of the poetic genre can be attributed, of course, to the book of Psalms, but there is also a great deal of poetry found in books that otherwise fall under completely different genres of literature - especially within the Prophets. In fact, when God’s voice is recorded in Scripture, it is most often recorded in poetic form.

Poetic literature is the response of genuine worship and praise to the truth of who God is. As such, it is intended to be experienced and meditated upon more than picked apart and studied. It contains rich illustrations, beautiful imagery, and masterful poetic structure to bring us into God’s presence in a state of awe and surrender. The best way to respect this genre as you read is to simply enjoy it and to let it work in you.

Lament

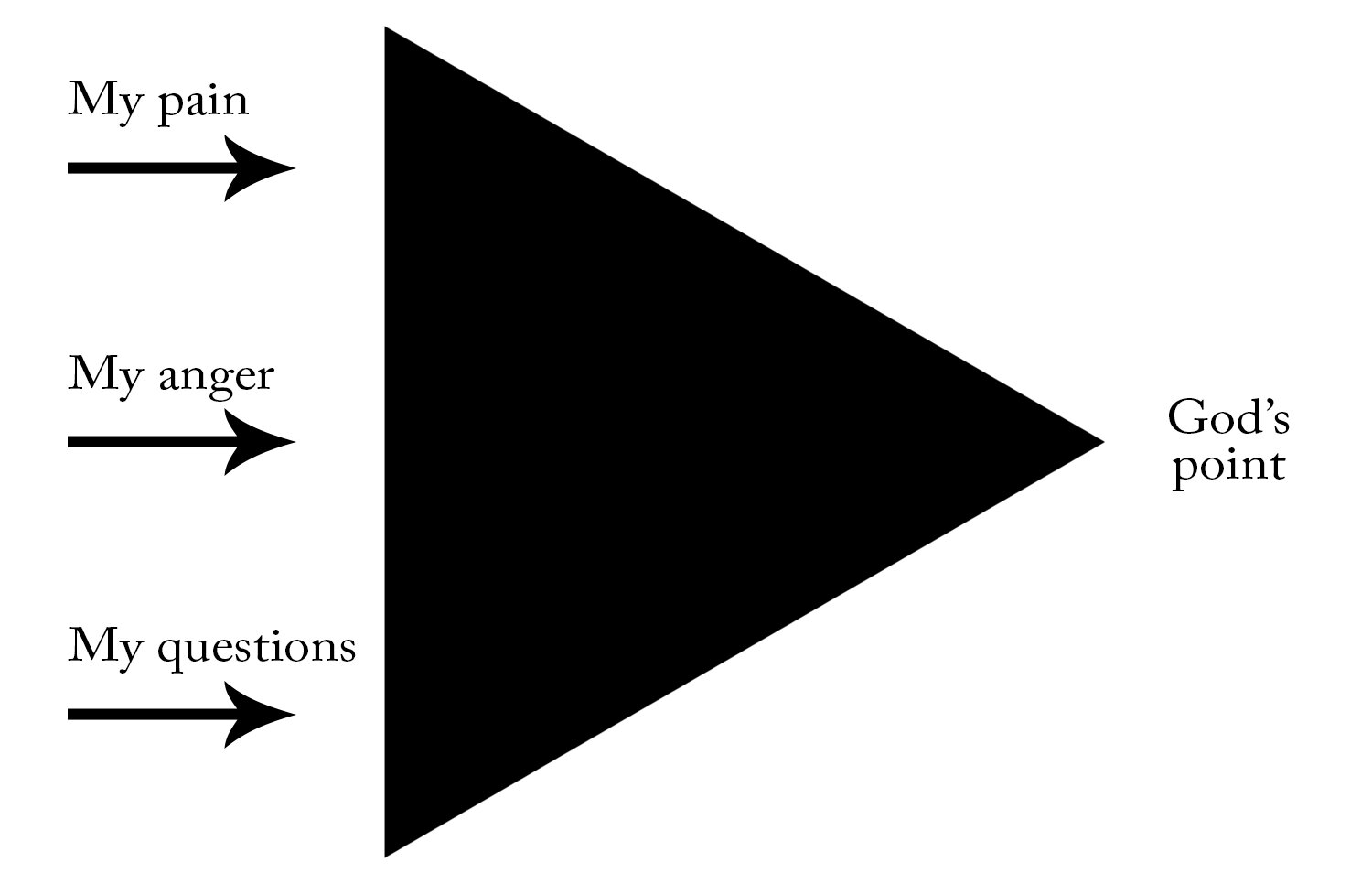

Lament is a specific type of poetry that follows a unique structure:

Lamentation literature embodies the process of being vulnerable with God so that He can reshape the writer’s outlook. It’s a poetic expression of grief, pain, anger, injustice, and any other difficult emotion, which are then submitted to God for the comfort and correction offered by His character.

Key to the careful reading of lament is remembering that many of the things the author writes, though written from the heart, are not true. Habakkuk will accuse God of not paying attention to Israel’s distress, which is an accurate reflection of Habakkuk’s despair, but a false representation of God’s character. So when you read poems of lament in Scripture, make note of the turning point when the author’s perspective is shifted by God’s truth.

Prophecy

This sixth genre of Biblical literature is the one most of us would probably consider the most mysterious. It brings to mind images of multi-headed beasts or prophets being commanded to do extremely strange things. It may either seem entirely irrelevant to our time or cause us to obsess about the coming end.

Contrary to popular conception, however, prophecy is not chiefly about predicting the future. Rather, prophetic literature is the revelation of God’s perspective on humanity’s past, present, and future. We could call it “God’s view of the news” - some of it being the headlines of the future, but far more often the headlines of many centuries past. The true excitement of studying prophecy is not in figuring out the identity of the Antichrist, but in the opportunity to deep-dive into what the events of earth look like from a heavenly perspective, and what that teaches us about who God is.

When you’re reading through the books of prophecy, it’s helpful to remember that you’re dealing with a multi-layered text:

Epistle

Finally, our seventh genre of Biblical literature - epistle - is probably very familiar to most of us. These letters to various early churches and church leaders make up the majority of the New Testament and, often, the majority of teachings from the pulpit today.

The epistles are also often (but not always, as scholars of Paul well know!) some of the most straightforward texts in the Bible. They expound on the reality of Christ’s redemption and how the Church is meant to live in it.

Being straightforward does not make them simple, however. They work through extraordinarily complex arguments and issues surrounding topics that are still debated two thousand years later. For this reason, I recommend two reading habits to employ when you get to the epistles:

Read them out loud, preferably all the way through in one sitting. If you can’t manage the whole thing, split it up into the largest chunks you can manage. We are used to dissecting the epistles in tiny pieces, but those tiny pieces first need the context of the whole.

As you read, highlight or underline only the essential words. Ignore extra words, descriptors, qualifiers, and anything that doesn’t speak directly to the author’s main point(s). Those other words are no less important, but it’s easy to get lost in them and miss the forest for the trees if we don’t take care to notice exactly what makes up the author’s essential argument.

In closing

Below, you’ll find a chart of the genres of literature and which books of the Bible fall under each. Remember, this isn’t an exact science. Parts (or the whole) of some books can often be categorized under two different genres. I’ve simply placed them roughly under the headings that I think make the most sense for the way they are best studied.

To download a printable version of this chart, click here.

Remember, Step Two can be implemented on top of Step One right away, no matter where you currently are in your reading! If you’re joining us for the Bible180 Challenge, you may want to get a copy of the Bible180 Challenge Journal, which provides a really simple framework for your reading, inspired by the different genres and the reading hints I’ve suggested in this post.