how to study the Bible: make relevant connections

/In the history of this blog, three of the top five most-read posts have been related to the topic of knowing and studying God’s Word. I love nothing more than hearing someone say, “I’d love to know how to study the Bible for myself” - or, “I’ve been going to church and Bible studies for years but I’m just so hungry for MORE.”

The study of the Bible isn’t just for pastors and elders. God’s Word is not only accessible to those who spend a decade in seminary learning ancient languages. I’m thankful for the people in my life who showed me that I, too, could learn how to study it for myself - because I was (and still am) hungry.

If you are hungry, too, this series is for you.

(See Step One HERE, Step Two HERE, Step Three HERE.)

How to study the Bible

Step Four: Make connections.

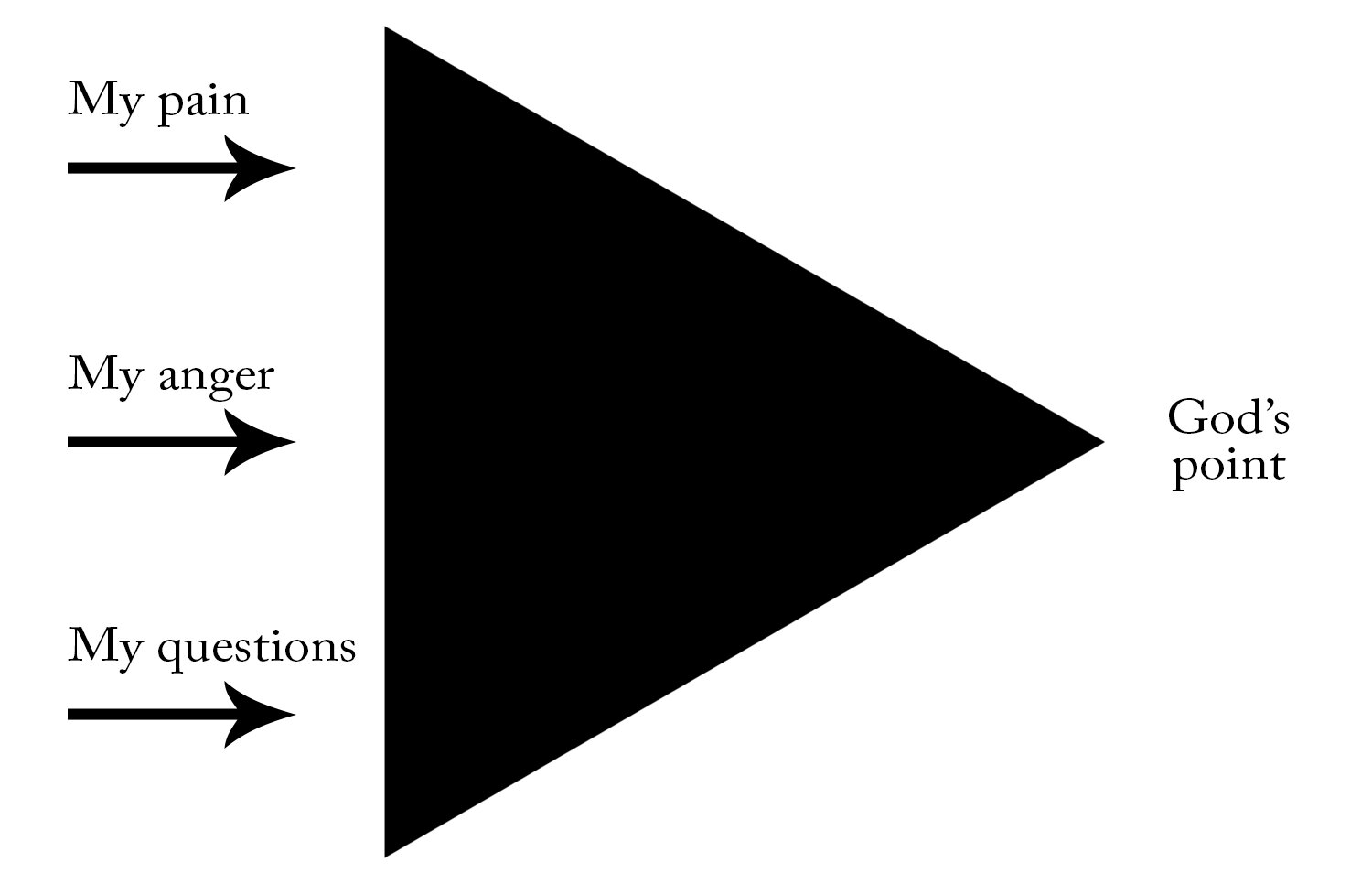

As you make progress on the first three steps, this fourth one becomes more and more important. The Bible is not a one-dimensional document to be read through once and journaled a little and then understood; it’s a stunningly multifaceted masterpiece of meditation literature. It’s meant to be read over and over, with new eyes for new revelation with each reading. Like a tapestry, thousands of colorful threads are woven together and interconnect at just the right places to make the portrait; like a gem, its countless facets shine and sparkle as we turn it in the light.

As you develop a solid study of this beautiful and complex work, you’ll need to learn how to observe and cross-reference these constant interconnections. The Bible is a story and a library, yes, but it’s also a magnificent piece of literary genius in which all 40+ authors write with the very breath of the Spirit to create a Book in which each piece adds a perfectly-fitting layer of meaning and depth to the whole.

Observe

The simplest way to begin is to pay attention. Is there a name in the passage that you’ve seen elsewhere - a person or place you remember from another chapter or book of the Bible, or a concept that was discussed in a preceding passage? What do you remember about it? Where can it be found in the Scriptures?

This is why I love color coding the narrative portions of the Bible. The colored highlights jump off the page, making it easy to scan for the names and places I’m looking for. The narrative of Israel’s history in the Bible spans centuries, yet many of the same players remain important throughout, which you’ll begin to notice when you start observing connections.

Cross-reference

Cross-referencing is a way of keeping these observations organized so you can continually refer back and forth among them. Many Bibles do some of the work for you by providing a list of cross-references in the margin, but I love to do it myself - it’s a way of keeping track of how my own study has developed over time. Every time I notice a theme, term, or idea in a passage that I remember from another passage, I try to write the reference of the other passage in the margin of the current one, and vice versa. Slowly, over the course of years of study, I am building a map through the tapestry that is my Bible.

Note: You don’t have to have a perfect memory to do this successfully. I don’t - God bless Google! Usually I can only remember a fragment of the connected verse, so I Google search that phrase to find the appropriate reference.

Dig Deeper

Observing and cross-referencing is plenty to keep you busy, but there will be times when you keep running into a word or concept that is difficult to understand, or you just want to know better. So this is going to be a very quick crash course in one of my favorite Bible study tools on the Internet: BibleHub.com.

I use this website weekly, if not daily. It’s certain to be open when I’m researching a passage I want to write about. It is truly a wealth of tools just waiting to be discovered, but for now I’m just going to introduce you to six of them:

The search bar. Obviously, this is where you enter the verse or passage reference you want to study.

Usually, the next thing you’ll see will be the verse you searched in parallel translations. This is a good, quick way to figure out if there is a pretty universal consensus on how the verse should be translated, or if there is some dispute.

There is a whole series of other tabs you can choose after Parallel, but the one I most often go to is the Strong’s tab. Here, you’ll find each word or phrase of the verse linked to its number in the Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance. If there’s a particular term you’re struggling with, click its Strong’s number and you will be taken to an entire page with its definition, uses, and cross-references throughout Scripture.

There is also a Commentary tab, if you’d like to read several commentaries on the verse or passage side-by-side. I don’t use this one as much, but it can be helpful if I’m feeling stuck and need different perspectives.

The Interlinear tab is another favorite. It gives you the verse in five different lines: The Strong’s links, the transliteration from the original language, the verse in the original language, the verse in English, and finally, each word’s grammatical part of speech.

Finally, possibly my number-one go-to is the Lexicon - mostly because it’s a bit more concise than the Interlinear and yet still hyperlinked to the Strong’s if I need it. It offers the verse in a set of four columns: The first is for the English, the second for the original language and its transliteration, the third for the Strong’s number and a brief definition, and the fourth for the linguistic origins of the word.

See the graphic below for a visual representation of where to find these tools on BibleHub’s homepage. (Click on the image to see it larger.)

Again, this is barely the tip of the iceberg of what BibleHub can do, but it will definitely get you started on a fruitful journey of making connections throughout the Word.

In closing

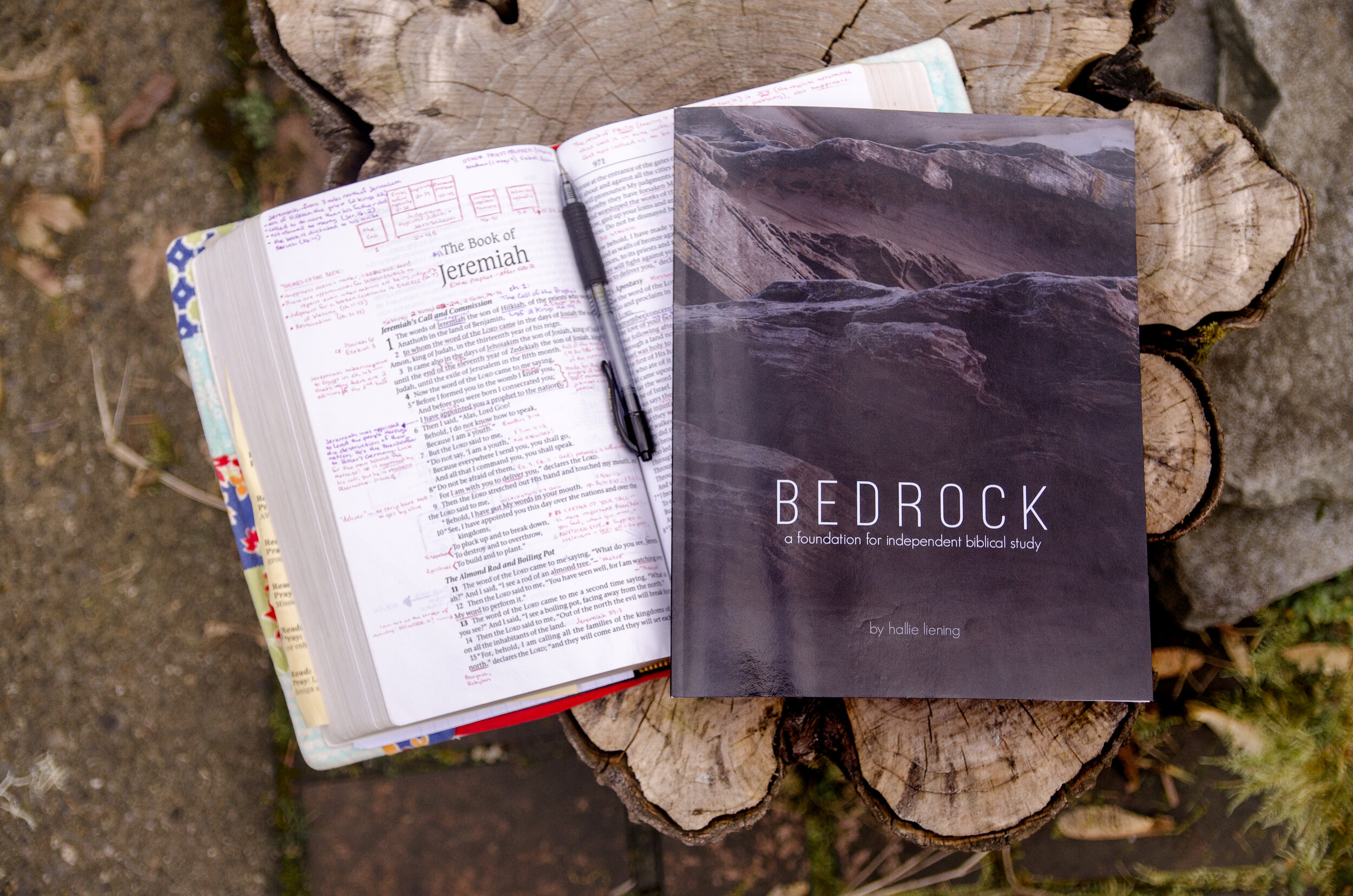

I hope this series has been helpful to you so far! We have just one more step to go in this overview of how to study the Bible. Remember, the Bible is an incredibly complex book, and there’s no way to exhaustively cover how to study it in a five-part blog series. People spend years in graduate school and still barely scratch the surface of the riches of the Word.

But I fully trust that God gave us His Word because He wanted us to know Him, not because He wanted to confuse us. I believe we can all mine its riches even if we never get to go to seminary. I believe that these five steps will help you lay a foundation of study that He can richly bless.

If you want extra guidance getting started, I highly recommend joining the Bible180 Challenge this coming year. We read together to stay accountable, and I send out weekly study resources to help everyone dig as deep as they’d like to. I’m also offering a completely offline tool - the Bible180 Challenge Journal - which is like a jumpstart guide on all five of these steps, and will allow you to start building great study habits on your own, right away. If you’d like to learn more, click here.